We use the term risk all too casually, and the term uncertainty all too rarely.– John Bogle

In 1969, IBM directed San Jose project manager Kenneth Haughton to develop a “direct access storage facility” that matched the performance of the high-end IBM 3330 system at a price attractive to low-end System/370 customers. The IBM3340 hard disk drive (HDD), which began shipping in November 1973, introduced a new, low-cost, and low-load design with read/write heads that landed on lubricated disks, establishing what became the leading HDD technology. Based on the original specification of a system with two spindles, each holding a 30 MB disk, Haughton noted, “If it’s a 30-30, then it must be a Winchester,” referring to the .30-30 Winchester rifle cartridge. Industry observers identified this new “Winchester head” as one of the four most essential developments in mass storage. The IBM Model 3350, introduced in 1975, transformed the data module into a non-removable head disk assembly with a 317 MB capacity, a design that some call “the real Winchester,” which has remained the fundamental HDD packaging concept to this day.1

From 1977 to 1984, venture capital firms invested nearly $400 million in 43 Winchester disk drive manufacturers across 51 different financing rounds, with 21 classified as start-up or early-stage investments. Most of this investment, $270 million, occurred in 1983 and 1984. During this period, the hard disk drive industry experienced rapid growth, with OEM market sales rising from $27 million in 1978 to $1.3 billion in 1983, and expected to reach $2.4 billion in 1984 (an 84% increase). Projections also forecasted that the market would surpass $4.5 billion by 1987. The enthusiasm in venture capital and stock markets for Winchester disk drive manufacturers, driven by optimistic industry forecasts, masked a phenomenon later known as “capital market myopia.” Fundamentals sharply declined in late 1984, with the combined market value of twelve key disk drive companies dropping from $5.4 billion to $1.4 billion.2

Individual investment decisions, which seem rational on their own, can often collectively lead to poor outcomes. When viewed alone, each investment decision appears justified. Together, these decisions form a recipe for investment pain. Investors, fixated on potential gains, overlook clear warning signs, in this instance, the overvaluation and overcrowding of the Winchester disk drive industry. Market participants should have foreseen the sector’s collapse, but the fear of missing out (FOMO) is a timeless and compelling emotion. This pattern frequently repeats itself, driven by the “greater fool theory,” an investment concept suggesting that an asset’s price can be driven higher by speculative demand, even if its intrinsic value is questionable. Investors always believe they can sell the “investment” later to a “greater fool” at a higher price. It relies on the assumption that there will always be someone willing to pay more, regardless of the asset’s fundamental worth.

The boom and bust of the Winchester disk drive industry from 1977 to 1984 parallels the explosive growth of the artificial intelligence (AI) and data center markets of today. The global AI semiconductor market was valued at $56 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach $232 billion by 2034, a compound annual growth rate of 15.2%. Data center demand for AI workloads has surged, with Nvidia reporting a 73% year-over-year increase in data center revenue to $39.1 billion in the first calendar quarter of 2025. Like the Winchester disk drive of fifty years ago, hyperscalers (large-scale cloud service providers) and GPU cloud providers, such as CoreWeave (CRWV), are rapidly expanding their capacity to meet industry forecasts. Nvidia’s (NVDA) dominance in AI GPUs has driven its equity market capitalization to $3.9 trillion, equal to the market capitalization of the entire German stock market.

In the 1985 paper “Capital Market Myopia,” written by William Sahlman and Howard Stevenson, the authors analyze the boom and bust of the Winchester disk drive industry. They note that winners and losers are determined by one’s ability to navigate irrational exuberance caused by collective investment decisions that ignore industry fundamentals. The clear winners were the venture capitalists who invested early in disk drive companies and investment bankers who facilitated the emerging industry’s initial public offerings (IPOs). Early investors reaped massive profits by capitalizing on the market’s euphoria. For example, Seagate’s venture capitalists invested $1 million for 17% of the company, which was worth $32 million post-IPO in 1980, when Seagate’s market valuation reached $185 million—a ridiculous valuation multiple of eighteen times trailing twelve-month sales. Investment bankers profited from over $800 million of industry underwriting fees. Winners also included founders and executives of disk drive companies who leveraged the hot IPO market to sell shares at peak valuations. Interestingly, the authors praised company executives who raised money at rich valuations, as the industry required heavy external capital due to high fixed assets and working capital needs.

The Winchester disk drive bubble also created many losers, particularly investors who bought disk drive stocks in 1983 at peak valuations. These investors faced massive losses when market values collapsed 74% from $5.4 billion to $1.4 billion by late 1984. Irrational exuberance and the “greater fool theory” overlooked industry overcrowding, with over seventy disk drive companies competing for market share, and unsustainable fundamentals. The disk drive industry, and by extension, U.S. technological competitiveness, also suffered as a result. This investment pattern will eventually apply to popular sectors in today’s market, including AI semiconductors, data centers, renewable energy, and battery storage, where early investors benefit from the “greater fool theory.”

A year ago, the excitement surrounding AI faced a harsh reality check on Wall Street. Goldman Sachs’ head of equity research, Jim Covello, questioned whether companies planning to invest $1 trillion in building generative AI would ever see a return on their investment.3 Venture capital firm Sequoia estimated that technology companies needed to generate $600 billion in additional revenue to justify their increased capital spending in 2024 alone, about six times more than they were likely to produce. These warnings sparked the first test of investment sentiment. Revenue from end customers, who hoped to benefit from this new technology, was minimal—there are no definitive generative AI “killer apps” on the market yet. A year later, leading AI stocks hit new all-time highs. Overcoming worries that started earlier in the year with the low-cost Chinese competitor DeepSeek (DEEPSEEK), Nvidia rebounded to set a record high, adding $1.5 trillion in stock market value from its April low, while Microsoft (MSFT) added $1 trillion in market value. Still, little has changed in AI’s broader revenue prospects since last year’s warnings. The optimism and hype remain as strong as ever, and it’s still difficult to see where future returns will justify the massive capital investments in AI, at least in the near term.

Resurgent optimism should come as no surprise. After all, in America, one can walk into a casino and bet one’s life savings on red or black. Whether it’s a bug or a feature, there is something to the American spirit that seems to sit more comfortably with investment risk than anywhere else. Naturally, Wall Street takes full advantage of our tendency to take risks. Wall Street is currently launching exchange-traded funds (ETFs) targeting speculative assets like smaller cryptocurrencies, meme coins (e.g., Dogecoin, $TRUMP), and even companies tied to “reverse-engineered alien technology,” driven by retail investors’ appetite for exotic investments. The surge in ETF filings, including a UFO Disclosure AI-Powered ETF, acknowledges Wall Street’s mastery of the “greater fool” theory.4

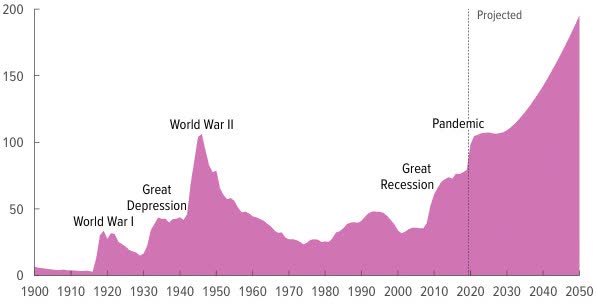

One typically associates capital market myopia with microeconomics, but one wonders if there is some application to the macroeconomic picture. There is little doubt that the United States is a going concern, but its financial operations do raise questions. The U.S. government received approximately $4.9 trillion in revenue but spent $6.8 trillion. Despite the enormous gap between operating revenue and expenses, the U.S. government finances itself without issue. The primary concerns focus on the future. The U.S. Treasury owes $37 trillion, gross, including $9 trillion to foreign holders of U.S. debt. Brett Loper, executive vice president for policy at the Peter G. Peterson Foundation, recently summarized the state of fiscal policy, “Even keeping Medicare on autopilot and Social Security on autopilot and Medicaid on autopilot, not making any changes, increasing or decreasing the cost of those programs, you’re looking at an amount of debt increasing by $22 trillion over the next ten years just to fund the government. You’re talking about the cost of interest payments on the debt doubling. Interest payments this year are going to cost more than the entire amount we spend on national defense, and yet they’re going to double over the next ten years. If you think of interest payments on outstanding Treasury debt as a program of the federal government, it’s the fastest-growing program in the federal government.”5

Federal debt held by the public is projected to equal 195% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2050, and the deficit is projected to equal 13% of GDP. Source: CBO

Each President and member of Congress makes budget decisions, which seem rational on their own, but collectively often lead to a poor outcome. The U.S. Congressional Budget Office provides nonpartisan budgetary and economic analysis to support Congress in its legislative and budgetary decisions. However, it also enables these individual budget decisions by making no allowances for wars or economic recessions—the CBO assumes that government borrowing costs will remain at interest rates ranging between 3.4% and 3.6% indefinitely. Credit rating agency Moody’s finally joined Standard & Poor’s and Fitch Ratings in downgrading the country’s credit rating on May 16. Not to worry, though, the S&P 500 closed up on that day.

As demonstrated during the 2008 financial crisis, credit agencies tend to be backward-looking. The capital markets already know the United States is not rated AAA. Insurance on U.S. sovereign credit trades at the same level as Greece and Italy. Critically, credit rating agencies play a crucial role in perpetuating the “greater fool” theory by maintaining the narrative that U.S. financial assets are accurately priced at their intrinsic value. Wall Street exploits the credit agency narrative to sell investment products that often lack factual or logical integrity. In his masterpiece book The Price of Time, Edward Chancellor provides a scathing summary of the current investment landscape:

“We have come to live in a controlled environment, with its fake money, fake interest rates, fake economy, fake jobs, and fake politicians. Our bubble world is sustained by a combination of passive acquiescence and powerful vested interests. It’s a 24/7 show with a global audience. Since risk is controlled, we have nothing to fear. Any departure from the bubble threatens a crisis. Extreme measures are adopted: negative interest rates, limitless amounts of quantitative easing. Too much is at stake to let the bubble burst.”6

The task of the investor is to discern value amidst the various narratives propagated by Wall Street, recognize the disconnect between hope and reality, understand why it exists, and then uncover the truth. The investor’s objective is to capitalize on the disparity between price and value. Unfortunately, most investors lack the temperament to resist the siren’s call to speculate. Anybody who operates in the investment industry long enough recognizes that market behavior often seems to come straight out of Alice in Wonderland. In few other areas of everyday activity is one so often invited to believe that what seems “good” is in fact “bad,” and vice versa. Declaring “Liberation Day” for import tariffs is bad, but deferring any decisions for ninety days is good; massive deficit spending is bad for the country but great for corporate profit margins; the Federal Reserve increasing interest rates to combat inflation is bad but lowering interest rates because of a stagnant economy is good.

Not surprisingly, this Alice in Wonderland behavior tends to baffle ordinary investors, reinforcing the notion that there is some mystique about financial markets that the ordinary investor cannot comprehend. Adding to the confusion is that Wall Street purposely obscures the difference between an analyst and an advocate. To an analyst, being wrong is disappointing, but it also presents an opportunity to learn—an essential element in a feedback loop of continuous improvement. Not so for the advocate. The advocate ties their profit motives to a specific outcome and feels compelled, whether consciously or not, to rationalize away or attack inconvenient realities. It is advocacy when each moment of unfavorable market price action is met with a cacophony of calls for central banks and politicians to act. In truth, there is no mystery to the investment process. Benjamin Graham provided investors with a path over seventy-five years ago to navigate the investment landscape. Graham, considered the father of value investing and author of the 1949 book “The Intelligent Investor,” provided a simple yet elegant set of principles for investing.

Graham generally focused on selecting securities representing what he deemed a sound business, particularly one with a strong balance sheet. While the business may be sound, Graham knew the market could not be relied upon to value it correctly at any given point in time. In times of market stress, sound companies can easily fall prey to a panic that envelops the broader market and captures investor psychology. Conversely, in times of high confidence, such companies may be seen as ‘boring’ when fast-paced growth is all investors care about. Graham believed the key to ensuring the scales were tipped in his favor lay in making certain that, no matter how sound the company, it should never be purchased at too high a price – a consideration many investors, particularly during times of speculative excess, forget. Graham termed this difference between what he paid for a stock and what he believed its true, intrinsic ‘value’ to be as the ‘Margin of Safety.’

Although the paper “Capital Market Myopia” about the Winchester disk drive industry was published nine years after Graham’s death, he would have immediately recognized this period as a classic case of speculative excess driven by irrational exuberance, a phenomenon he repeatedly cautioned against. The Winchester disk drive industry’s 74% crash exemplified his warnings about Mr. Market’s irrationality and the dangers of speculation. Graham’s investment principles stand the test of time. In 1974, Forbes magazine interviewed several grizzled veterans of the Wall Street investment community, contemporaries of Graham.7 They had lived through both good times and bad, gaining a perspective that only age and experience can provide. Each had been quite successful in their long investment careers. They were all fundamentalists who purchased solid companies in solid industries with solid management and solid balance sheets.

While none of the veteran investors allocated all their capital to common stocks, they all possessed the emotional discipline to ride through decades of stock market volatility. At age 71 (1974), Joseph Nye retired from Wall Street when he sold his New York Stock Exchange seat for $205,000 in 1972, but did not retire from investing. Nye reflected on his investment career, “You know, most people don’t know what stands behind their investment in common stocks. We do. We’re careful to the point of thoroughness.” Bradford Story, who graduated from Yale University in 1923, and was the last surviving founding partner of Brundage, Story & Rose, a conservative investment counseling firm at 90 Broad Street, noted that “We take the risks of the capitalist, but never the risks of the Wall Street man. The capitalist takes industrial risks, not financial risks.” In other words, Story looked for strong companies, not stock market quotations. When the article’s author asked Story about quarterly earnings as an investment guide, he replied, “Once you buy earnings, you become a cheap little guesser.”

Over the decades, Nye and Story watched many of their colleagues get into trouble and go under. Men like Nye and Story accepted their investment mistakes with dignity but took the opportunity to learn from their mistakes. They were realists rather than optimists or pessimists. In traditional societies, concluded the Forbes article, the young learn from their elders. By contrast, Wall Street tends to listen to youth, not age. Youth is fine when there are abundant opportunities. Youth possess the energy and drive to take full advantage of these possibilities, but the young can offer no guidance when times grow tough—it is a new experience for them. Then the statesmen, the village elders, the “grandfathers” come into their own.

The United States has been blessed with an abundance of resources and prosperity for so long that it is almost unimaginable for an investor today to contemplate the investment landscape of the 1930s. One thing repeatedly emphasized by the old investment veterans was the lack of cash to buy stocks when they traded at bargain prices. Nobody had any money. The combination of a 90% market decline and widespread bank failures in the early 1930s resulted in the destruction of people’s savings. The banks that did not fail froze their customers’ savings accounts and imposed daily withdrawal limits on the amount of money a customer could withdraw. In some cases, it was as low as 5% of the money in their account. Some were so desperate for cash that they sold their bank passbooks (a record of their account, if one is old enough to remember) at 50% or less of the amount in their account to get cash. And that was not uncommon—the newspapers provided daily quotes on bank passbooks.

The investment elders also noted that people failed to learn from the 1929 crash. They knew of many Wall Street colleagues who lost everything in the 1929 crash, only to repeat the same mistake four or five years later. Several of their colleagues bought stocks near the lows of the Great Depression, rode the recovery, and made a small fortune again. But rather than sell, they got greedy. They maxed out their accounts on margin to buy more stocks, only to watch the market turn and wipe them out again. The power of desperation and greed over rational investment decisions is timeless and hard to overcome. Evolution has hardwired these emotions into humans. A mindset centered on capital preservation is crucial for surviving and prospering over many decades of investing in the capital markets.

The principles of conservative investment apply whether one buys real estate, stocks, bonds, or companies like those producing Winchester disk drives in 1984, or the generative AI companies of today. A careful analysis of the company’s fundamentals is essential, with the safety of one’s principal always at the forefront of any investment decision. Seeking abnormally high returns invites greater risk and speculation. In Benjamin Graham’s writings, he repeatedly emphasized that avoiding catastrophic losses was crucial for any investor aiming to achieve steady compounded returns throughout their investment career. Such losses place the investor in an unenviable position; they try to chase performance to recover to their previous level of capital.

During his 2005 commencement speech at Stanford University, Steve Jobs used the phrase “You can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backwards” to convey that life’s path and the significance of events often only make sense in retrospect. When making decisions, whether about career, education, or personal pursuits, Jobs knew he could not predict with certainty how these decisions would lead to future outcomes. Instead, clarity emerges later, when one reflects on how seemingly unrelated experiences, choices, or mistakes fit together to shape one’s life journey. Jobs illustrated this with his own life—he dropped out of Reed College and took a calligraphy course, which seemed aimless at the time but later influenced Apple’s focus on typography and design.

Jobs advised the new graduates to trust the process and follow their curiosity and intuition. The “dots” represent key moments or decisions that eventually align in ways one cannot foresee. As an investor, one must make the best possible decisions based on the information presently available. In hindsight, everything often seems logical, but looking ahead is always filled with uncertainty. Investment survival requires a disciplined, conservative approach. Investment mistakes can prove quite painful, but they also offer an opportunity to reflect and learn. Successful investors must remain hungry to learn, to read, to listen, and try to connect the “dots.”

With kind regards,

St. James Investment Company

Footnotes

1https:// www.computerhistory.org/storageengine/winchester-pioneers-key-hdd-technology/.

2William Sahlman and Howard Stevenson, “Capital Market Myopia,” Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 1, 1985, pages 7 – 30.

3Will the $1 trillion of generative AI investment pay off?

4https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1771146/000121390025009523/ea0229673-01_485apos.htm

5“Once Said, Can’t Be Unsaid” Grants Interest Rate Observer, Vol.43, May 9, 2025.

6Edward Chancellor, The Price of Time: The Real Story of Inter est, New York, Atlantic Monthly Press, 2022.

7“The Grandfathers,” Forbes, September 1, 1974, Pages 28 – 31.

|

St. James Investment Company We founded the St. James Investment Company in 1999, managing wealth from our family and friends in the hamlet of St. James. We are privileged that our neighbors and friends have trusted us to invest alongside our capital for twenty years. The St. James Investment Company is an independent, fee-only, SEC- registered investment Advisory firm that provides customized portfolio management to individuals, retirement plans, and private companies. Disclaimer Information contained herein has been obtained from reliable sources but is not necessarily complete, and accuracy is not guaranteed. Any securities mentioned in this issue should not be construed as investment or trading recommendations specifically for you. You must consult your advisor for investment or trading advice. St. James Investment Company and one or more affiliated persons may have positions in the securities or sectors recommended in this newsletter. They may, therefore, have a conflict of interest in making the recommendation herein. Registration as an Investment Advisor does not imply a certain level of skill or training. To our clients: please notify us if your financial situation, investment objectives, or risk tolerance changes. All clients receive a statement from their respective custodian on, at minimum, a quarterly basis. If you are not receiving statements from your custodian, please notify us. As a client of St. James, you may request a copy of our ADV Part 2A (“The Brochure”) and Form CRS. A copy of this material is also available on our website at www.stjic.com. Additionally, you may access publicly available information about St. James through the Investment Adviser Public Disclosure website at www.adviserinfo.sec.gov. If you have any questions, please contact us at 214-484-7250 or [email protected]. |

Original Post

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Read the full article here