June’s FOMC meeting brought traders the long-awaited pause in the Fed’s interest rate hiking campaign. However, the pause came with a kicker– FOMC members raised their projections for this year’s inflation and raised their projections for interest rates for 2023, 2024, and 2025. The Fed’s Summary of Economic Projections, better known as the “dot-plot,” showed a broad consensus for hiking interest rates twice more in 2023.

- Additionally, we can infer from the dot plot that the Fed is looking for interest rates to exceed core inflation by roughly 2% annually until inflation is returned to its 2% target.

- Powell’s rhetoric at the press conference was a bit softer and somewhat contradictory, where he indicated that the Fed is “pausing” and not “skipping,” and that a July rate hike has not yet been decided. Futures markets show a roughly 70% chance of a July hike at this time.

- However, Powell indicated that rate hikes would not be appropriate in 2023, and even went as far as to say that rate cuts are “a couple of years out.” It’s not immediately clear whether the “couple of years” comment was intentional or if Powell misspoke.

- Reading between the lines here at what Powell might be hinting at, I believe this implies the Fed sees cuts sometime in mid to late 2024, with the cuts coming because the Fed doesn’t see a need for real interest rates to be higher than 2% or so (meaning if inflation is at 3.5%, rates should be at 5.5%, and if inflation falls to 3%, they can cut to 5%). This is still in sharp contrast with the medium-term view of the market, which sees the Fed cutting rates in 3-6 months.

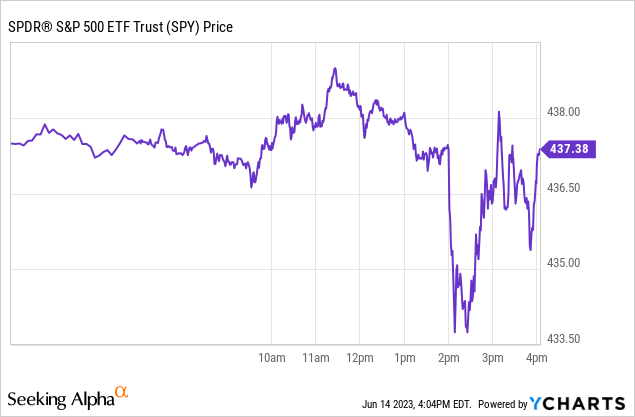

The Fed took the markets for a ride today, but stocks closed about where they started, as did bond yields.

Does The Fed’s Move Change Anything?

At the margins, yes.

FOMC members now expect interest rates at year-end to be roughly 50 bps higher than they did in March. This means cash (i.e. money market funds and CDs) that were projected to be paying around 5.25% are now likely to pay closer to 5.75%. Additionally, the Fed strongly pushed back on the idea that they would be cutting interest rates anytime soon.

If you take the Fed’s economic projections at face value, then cash is expected to pay 50 bps more than it did before the FOMC meeting, and credit is expected to similarly get more expensive. Additionally, these conditions are expected to be maintained for longer than markets had previously anticipated. On the other hand, valuations for stocks are roughly unchanged. The Fed’s move here does complicate the picture for stocks. The S&P 500 (SPY) is valued at about 20x earnings at the moment, while many Nasdaq (QQQ) stocks are trading at valuations only matched by the dot-com bubble. Even at valuations only matched by 1929, 1999, and 2021, traders can’t get enough of stocks.

The most important thing here about this FOMC meeting is that the Fed is providing a clear alternative to piling your money into stocks. If you don’t want to pay record valuations for stocks, then you have solid alternatives. Cash should pay 5.5-5.75% by year-end, corporate bonds will pay about the same for longer maturities, and high-yield bonds are paying over 8%. These are all senior to equities, meaning that by definition, equities will take huge losses before these take any credit losses.

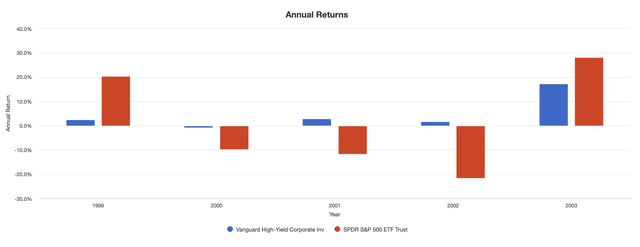

For a classic example, take a look at the comparison between the returns on an inflated S&P 500 from 1999-2004, and the returns of the Vanguard High Yield Bond Fund. As an aside, note that Vanguard’s high-yield bond fund doesn’t invest in deeply troubled companies, but rather seeks to maintain a lower-risk profile. Additionally, they’ve sharply cut their expense ratio over the years. These days, a lot of the really dicey stuff actually isn’t in the junk bond market, but rather in the leveraged loan market, and repackaged as collateralized loan obligations (CLOs). If the acronym CLO sounds sketchy, it’s because it is!

Anyway, the S&P 500 is in red, while high-yield bonds are in blue.

High Yield Bonds Vs. S&P 500 (Portfolio Visualizer)

High-yield bonds returned 4.5% annually from January 1999 to January 2004, while stocks made huge gains, only to plunge 50%. When it was all said and done, $100,000 invested in high-yield bonds ended the cycle at roughly $125,000 in value, while T-bills ended at about $118,000. Stocks finished the cycle at about $96,000, minus whatever those living on their investments needed to withdraw.

Take the sample out to January 2011, and stock investors end up behind high-yield bonds again. On a risk-adjusted basis, the bonds did better around the same time equity valuations started to get crazy. And when stocks launched the epic 2010s bull market, they started from very cheap levels after the global financial crisis. All of these calculations assume that investors don’t respond to crashing stock valuations by buying low. Successfully doing so is likely to add greatly to your return potential. It’s not market timing, per se, rather you’re taking whatever the market is offering you when cash/bond rates and P/E multiples are high or low.

What if we go back to Greenspan’s “irrational exuberance” speech in December 1996? Then, stocks were actually cheaper on a P/E basis than today. The story then is a little better for stocks, but equity investors still ended in roughly the same spot as high-yield bond investors, after pulling ahead in early years and falling behind late. The S&P 500 also was helped greatly by a trio of tax cuts pushed through first by Bill Clinton and then by George W. Bush.

Most sober-headed investors understood that market hype was overdone in the late 1990s, especially since cash rates were raised to over 6% by 2000. Even Jack Bogle timed the market then and sold stocks at crazy valuations. However, the S&P 500 continued to soar longer than investors thought. But when the crash did come, taking less risk turned out to be prudent. As long as you were smart enough to put your money where it earned yield in the 1990s, then you came out a big winner by refusing to overpay for stocks, and then buying them when they eventually crashed. Even if you didn’t, most investors still came out ahead.

The Fed Doesn’t Care About The NASDAQ

The definition of an asset price bubble is when assets rise in price without a rise in underlying fundamentals. For stocks, this means that prices skyrocket without a corresponding rise in earnings, or without any earnings at all. For example, Apple (AAPL) rising 47% this year while analysts downgrade their earnings expectations is generally indicative of a bubble. It varies in magnitude, but the story is more or less the same for the rest of big tech. One could say the same when companies with little to do with AI suddenly start pumping their prowess in artificial intelligence.

One question that I see investors ask a lot and one I’ve asked myself is whether the Fed should challenge speculative bubbles by hiking interest rates. Surprisingly, this topic has been heavily debated by senior policymakers over the years. For example, here’s a 2008 speech by Fed governor Frederic S. Mishkin. Mishkin argues that the Fed shouldn’t, but should respond to bubbles’ effect on aggregate demand. Current Minneapolis Fed president Neel Kashkari has published more recently in 2017 on the topic and made a progression of fairly nuanced arguments. Kashkari mostly agrees, but states that the Fed should perhaps react more strongly to bubbles that are fueled by debt rather than those that are pure speculation in the financial markets. In other words, real estate bubbles are much worse than stock bubbles.

Even then, there are tools other than raising interest rates that are better for slowing down speculation, such as raising required down payments on real estate. Raising interest rates tends to be a fairly blunt way to deal with asset bubbles, so it necessarily shouldn’t be used indiscriminately. Market observers consistently tend to draw a distinction between real estate bubbles and stock market bubbles. Paul Krugman wrote this about asset bubbles when he was an economics professor at MIT.

The thing to understand is that a stock market boom is not like a boom in physical investment – say, a boom in condominium construction. That kind of boom depresses future spending because it leaves behind a landscape littered with unsellable condos. But that isn’t quite what happens when stocks surge: When the market value of Croesus.com doubles, that doesn’t mean there will be an overhang of vacant dot-coms weighing down rental rates two years from now. It’s paper gains today, paper losses tomorrow; who cares?

“Who cares” neatly sums up the Fed’s general attitude to stock market bubbles. I had thought Powell should crush the speculators, but after reading the Federal Reserve research on the topic, I at least understand where the Fed is coming from. Here, they’re not dropping the hammer on bulls, but rather ignoring them while slowly, quietly raising the rate on cash to a level that offers an equal or better long-run expected value than stocks.

No one is forcing you as an investor to jam your money into Nvidia stock (NVDA) at 163x earnings as it hits 52-week highs each day. Pure financial market bubbles like those in the Nasdaq don’t create or destroy wealth, they simply redistribute it from one group of investors to another, minus the massive short capital gains taxes that they tend to create. Gambling money knows no home, and it’s likely that some investors will lose their shirts trading AI stocks, while others will gain. Research shows that rich, sophisticated households tend to win money from asset bubbles, while poorer and unsophisticated investors tend to lose. In this way, bubbles tend to redistribute large amounts of wealth from believers to skeptics.

Bottom Line

The bigger problem for the Fed isn’t the wild swings in the Nasdaq over the past 18 months, but that young households are increasingly ramping up their expenses and increasing their debt loads, possibly on the expectation that the government will bail them out if anything goes awry with the economy. The Fed can’t be happy with how fast credit card debt is increasing, how low personal savings rates are, and how stubborn inflation has been despite sluggish productivity. The housing market remains far out of whack, with typical mortgage payments for the US and UK frequently quoted at triple what they were a few years ago. For these reasons, the Fed will need to continue to hike rates to balance supply and demand. The Fed is offering a clear alternative to investors by signaling that they’ll raise risk-free interest rates on cash to 5.75% annually. But when you can make or lose 10% per day trading the Nasdaq-du-jour stock, not many people seem to be interested. At least not yet.

Read the full article here