[Please note that all currency references are to U.S. dollar)

Wheaton Precious Metals (NYSE:WPM) (TSX:WPM:CA) ($66.00) is a Canada-based precious metal streaming company. The company was founded in 2004 and is listed in Toronto, New York, and London. The headquarters is in Vancouver, Canada.

Wheaton is one of the prominent precious metals streaming companies with an impressive track record now approaching 20 years. The company’s philosophy of focusing on reputable counterparts with projects in the lower half of the cost curve has served it well over time. Still, occasional, but painful impairments appear from time to time in the financial statements and the return on equity remains low. Prospects for growth in production over the next 5 years are promising but conversion into profits depends on the prices of gold and silver at the time when the production is received. The high valuation leaves no room for production mishaps or lower precious metals prices.

The Wheaton business of streaming

The Wheaton streaming model entails the identification and contracting of appropriate mining production targets and the payment of upfront fees for the right to buy future production at pre-agreed prices. The key variables that influence the Wheaton results are the volume of metals production received by the company and the prices realized upon the sale of the metals.

The core focus of Wheaton is on gold and silver produced by high-grade mines operating in the lower half of the cost curve. By April 2023, Wheaton had contracts with 20 operating mines, 12 development projects, and 3 projects that have been placed on care and maintenance.

In 2022, Wheaton received 638,113 ounces of gold equivalent (“GEOs”) production. This was made up of 24 million ounces of silver, 286,805 ounces of gold, and 27,069 ounces of other metals. Revenue from gold sales made up 50% of its revenue, silver 44% with the balance coming from palladium and cobalt sales.

In 2022, 40% of the GEO equivalent production was produced by mines in North America, 51% in South America, and 10% in Europe. Just over 90% of the GEO production came from mines that operate in the lower half of the cost curve.

Vale is the largest counterparty and was responsible for 34% of Wheaton’s revenue in 2022, while Newmont provided 16% of the company’s revenue.

The largest of the contracts is currently with Vale for gold production from the copper mining Salobo project in Brazil. The mine started with a throughput capacity of 12 million tonnes per year (“Mtpa”) that was subsequently expanded to 36 Mtpa. Starting with a first payment in 2013, Wheaton paid a total of $3.1 billion in exchange for 75% of the gold production over the mine’s life and a per unit payment production payment of $416 per ounce.

Another major contract is with Newmont Corporation for silver production from the Penasquito mine in Mexico. Penasquito is the largest gold mine in Mexico; in 2007 Wheaton paid $485 million for 25% of the life of the mine’s silver production and a cash payment of $4.43 per ounce.

A profitable business but with considerable variability

The business of commodity mining comes with significant risks including exploration and technical mining risks, and profit variability as commodity prices move through cycles. Against that background, Wheaton has performed well by remaining profitable, except for 2015, since its public listing in late 2004. Cash flow from operations remained consistently positive.

Wheaton has also grown substantially over the past two decades. Sales of GEOs moved up from 50,000 in 2005 to 620,000 in 2022 although the sales volumes remained fairly constant since 2016. Operating cash flow also increased from $30 million in 2005 to $744 million in 2022.

Still, profits vary significantly from year to year. Earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization dropped by 40% between 2012 and 2015, and again by 25% between 2018 and 2019.

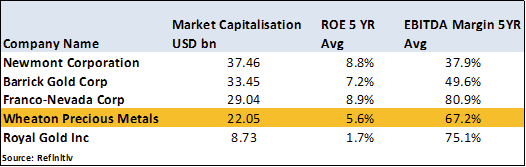

At the company level, operating margins averaged 48.3% over the past 15 years, with a peak of 77% in 2011 and a low of 31% in 2018, driven by precious metals price realizations. Despite the high profit margins, the return on equity was subdued, averaging only 5.6% over the past 5 years.

The table below compares the profitability of Wheaton with another major streaming company, Franco-Nevada, as well as the major precious metals producers. Despite the high-profit margins achieved by these companies, the return on equity remained subdued, likely the result of high capital outlays.

refinitiv

In addition to the streaming contracts, Wheaton also holds direct minority investments in mining companies such as Hecla, Sabina, and Bear Creek. These investments were valued at $256 million at the end of December 2022.

Risks: Watch out for the taxman

The business of commodity mining carries significant operational and financial risks. However, the streaming companies are in a position to lower these risks by carefully selecting projects advanced by reputable mining companies, that have the prospect of operating in the lower half of the cost spectrum.

Still, the streamers also take on considerable risks, which include fluctuating commodity prices, poor execution by the mine operators, incorrect production and reserve estimates, and governmental, political, and environmental risks.

While Wheaton has fared well in managing these risks we note significant impairment charges that appear from time to time on the income statement. In 2015 the company wrote off $385 million (related to its investment in the Pascua-Lama project in Chile and the 777 project in Canada). In 2016 the impairment charge was $71 million (Sudbury project owned by Vale). In 2017 there was an impairment charge of $229 million (Pascua-Lama) and $166 million in 2019 (related to the decline in the cobalt price, which impaired the investment in Voisey’s Bay; however, this was reversed in 2021 when the cobalt price increased).

The company pays almost no corporate tax as a result of the tax-free Cayman Islands domicile of it fully-owned subsidiary, Wheaton International. Wheaton runs most of its income-generating activities through the subsidiary. Still, the Canadian Revenue Agency has challenged the tax position of Wheaton resulting in a settlement in 2018. Under the terms of the settlement, Wheaton paid additional taxes and penalties of $8.3 million while the CRA agreed that profits earned by Wheaton’s foreign subsidiaries will not be subject to income tax in Canada.

Wheaton reported in 2022 that the CRA issued notices of reassessment for the 2013-16 tax years related to the taxation of its investments in Canadian mining assets. The company expects additional charges from the CRA of $2 million related to these reassessments.

Growth prospects – locked in

In its 2022 and 2023 federal budget statements, the Canadian government announced its support for an OECD initiative to apply a 15% minimum tax on the income of large multinational companies. This will likely impact Wheaton from 2024 onwards.

Wheaton estimates that its current portfolio has over 30 years of mine life based on proven and probable reserves. After years of stagnant production, the company now expects to receive GEO production of 810,000 oz per year on average over the next 5 years. That will be about 25% more than the 638,000 oz of GEOs received in 2022 and the midpoint of the 600,000-660,000 ounces expected for 2023.

Growth should come from additional production at contracted projects such as Salobo, Voisey’s Bay, Stillwater, and Constancia, or new projects launched by Copper World, Blackwater, and Toroparu. Although Wheaton already has pre-committed contractual obligations of $1.62 billion until 2025, further acquisitions are also possible supported by the company’s strong balance sheet and cash flow (see below).

Corporate governance: Long-serving CEO

The chair of the board is George Brack (age 61), who has been on the board since 2009. His industry experience includes roles at Scotia Capital, Macquarie North America, Placer Dome, and CIBC Wood Gundy. He has wide-ranging experience in investment banking and holds degrees in geological engineering and business administration.

Randy Smallwood (age 58), has been the President and Chief Executive Officer since 2011. He has been involved with Wheaton since its founding and joined the company full-time in 2007 as Executive Vice President of Corporate Development. He holds a geological engineering degree from the University of British Columbia and also serves as the Chair of the World Gold Council.

The directors and executive officers jointly own less than 1% of the outstanding common shares of the company. The major shareholders are institutional investors including Vanguard, Blackrock, Fidelity, and MFS.

Key aspects of executive compensation are a base salary, an annual performance bonus scheme, and a long-term incentive plan. The performance bonus scheme includes elements of growth related to the future delivery of precious metals, the financial and operational performance of the business, and environmental, health, and safety considerations. The “growth” leg weight for 2023 has been increased to 50% (from 40%) while financial and operational performance will be weighted at 15% and 20% respectively.

The President and CEO received a total compensation of $6.7 million and $6.3 million for the 2022 and 2021 fiscal years.

A debt-free balance sheet

The company had shareholders’ equity of $6.7 billion at the end of December 2022 while the net cash holdings amounted to $694 million. Net cash has grown significantly over the past 4 years while debt that amounted to $1.26 billion by the end of 2018 was eliminated courtesy of high levels of operating cash flows and limited acquisitions or capital payments.

Cash flow from operations amounted to $744 million in 2022 while the net cash flow from investing activities (including acquisitions and disposals) amounted to $45 million. The dividend absorbed $237 million resulting in a strong build-up of the cash balance.

The dividend depends on the cash flow

Wheaton links its dividend to the average of its fourth-quarter operating cash flow. This implies that the dividend is largely tied to the realized prices of silver and gold. The quarterly dividend amounted to $0.60 in 2022 for a current yield of 1.2%.

Outlook for 2023

Management expects to receive GEO production of between 600,000-660,000 ounces in 2023. This will be roughly the same as in 2022. The prices of gold and silver have increased in recent weeks but are not materially different from 2021.

Consensus forecasts indicate revenues, EBITDA, and earnings per share slightly higher in 2023 compared to 2022. However, as production ramps up later in 2023 and 2024, profits could move higher by 15%-20% depending on the realized prices at the time.

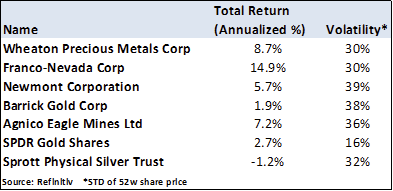

Streamers perform better than the producers and physical gold and silver

The main precious metals streaming companies (Wheaton and Franco-Nevada) have done very well over the past 10 years, easily beating the stock market returns of the major precious metals miners as well as physical gold and silver (see table). Also, when volatility is considered, the streamers were less volatile than the miners.

refinitiv

Expensive valuation

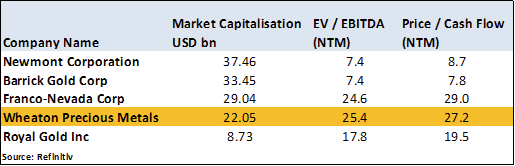

Given Wheaton’s current price and consensus forecasts for the next 12 months, the business is valued on an EV/EBITDA ratio of 25.4 times, and a price-to-cash flow ratio of 27.2 times.

Compared to the peer group indicated in the table, Wheaton’s valuation is on par with Franco-Nevada but at a considerable premium to the gold miners. Wheaton is also trading at a premium to its average 5-year EV/EBITDA valuation multiple.

refinitiv

Investors may have already decided that the precious metals streamers offer a better reward for the risk involved than the gold miners. However, the absolute valuation for Wheaton is high and the spread over the gold miners, is too wide, in our view.

It all depends on the precious metals prices

The financial and stock market performance of Wheaton depends on two key factors: the delivery of metals production from the contractual counterparts as well as the prices realized for these products on delivery. While the first factor can be predicted with some measure of reliability, the realized prices are not predictable. This leaves investors with a high level of uncertainty and risk – for which they are not compensated at the current stock price.

By Deon Vernooy, CFA, for TSI Wealth Network

Read the full article here